At dawn of March 13, 2023, the ‘Field Marshall’ died.

The sound of messages bombarding my phone woke me up that morning.

The first came from my former classmate and childhood friend, retired Director-General of the Nigerian Television Authority, and Captain of our football and athletics teams in St. Murumba College, Jos, Mallam Yakubu Ibn Mohammed, ‘Planner the Dazzler’, the man who dazzled with his feet as well as his brain whilst we were in school.

With his message came a flood of memories of Jos and of the Field Marshall.

I spent the first 17 years of my life in Jos, undoubtedly one of the most beautiful places on the face of the earth. Anyone that knew Jos before the internecine crisis of 1966 and even into the 1980s, would tell you exactly the same thing – Tin City was the best place to be born, to grow up, to work and to live a life in search of genuine happiness. The city had everything good as sample to offer the world.

Its climate was, and still is, one of the best in the world – cold for 2 months, cool for 2 months, mild for 2 months and warm for the two months preceding the rains, every year. Hailstorms of falling ice are not an uncommon occurrence.

Scooped as if with a spoon by some natural cataclysmic occurrence (a meteor or asteroid) in the distant past, Jos ‘sits’ in the resultant trough, a plateau ringed by dark rocky hills, some 2000 feet above sea level. The city and its surrounding villages are an enchanting landscape of rock formations, ravines, valleys, cascading waterfalls from huge boulders, and artificial lakes from old mines.

Around the city could be found some rare earth minerals. That explains why the city was a great attraction for foreigners prospecting for the rich minerals abundant in that environment. It was a city of miners burrowing the earth along meandering streams and riverbeds that often revealed the presence of Tin ore. That part of Nigeria used to have the largest reserves of Tin and Columbite in the world. They have all been mined and the deep abandoned holes created in the ground have all been filled by rainwater. The result is a mixed blessing. These deep and dangerous lakes of water have now altered irreversibly the landscape. At the same time, imaginative business adventurers have ‘tamed’ some of them and converted them into holiday resorts, with a warning never to swim in them.

The combination of rare minerals, great weather, a big railway terminus of trains from the East, the West and the North of Nigeria, and a small airstrip (now expanded into an airport) that could accommodate small aircrafts, made Jos a huge attraction for foreigners, miners and traders from all over the country. Jos had the biggest walled markets in Nigeria at a time in history.

The city was a melting pot of ‘migrants’ from all parts of Nigeria. The real owners of the land, the Biroms, were ‘invisible’, the smallest in population in the cosmopolitan town, quietly, happily and peacefully living their sheltered lives in their villages that are rich in exotic fora, fauna and arable land gifted them by mother nature.

Then, one day in January of 1966, politics descended on the land and shattered the tranquility of this masterpiece by the Creator. The destruction of this ‘Garden’ started with a pogrom that became one of the darkest chapters in Nigeria’s history. This model cosmopolitan city in the heart of Nigeria became the theatre of some of the most brutal vendetta killings, a field that is consuming the blood of thousands of innocent Nigerians in a senseless orgy of political, ethnic, tribal and religious differences.

Jos has been nursing this existential threat for decades, hurting and haunting without healing, even till now. Like a volcano, the horror erupts again from time to time from the bowels of hell rendering efforts to heal the wounds ineffective.

I grew up in that city seeing and experiencing both sides of the coin, the good as well as the ugly sides.

Incidentally, what Jos has never lost throughout its long sojourn in the dark tunnels, is its production line of some of the best footballers and long-distance runners in Nigeria. That tradition of breeding exceptional football players has sustained and remains a reminder that it could be one of the ‘soft tools’ to deploy in nursing the city back to good health. For those leaders that can see beneath the superficiality of sport as an ordinary game or recreation, and can look at its unifying, engaging and enriching powers, they just have to look closely at how to tap this resource to quench the fire still smoldering in Jos. Trust me, it can be done.

Jos has been producing some of the best and highest number of exceptionally gifted football players in Nigeria’s history.

It has probably produced more players for the national teams of Nigeria than any other town except, probably Lagos. These are great ambassadors.

I am surfing through the names of great football legends that passed through the ‘tutelage’ of Jos – Erewa, Mazelli, Tunde Abeki, Hudson Papingo, Fabian Duru, Christopher ‘Ajilo’ Udemezue, Godwin Ogbueze, Emmanuel Egede, Layiwola Olagbemiro, Gabriel Babalola, Peter Anieke, Tony Igwe, Samuel Garba, Amusa Shittu, Tijani Salihu, Joseph Agbogbovia, the Atuegbu Brothers, Sunday Daniel, Bala Ali, Wole Odegbami, Mikel Obi, Sam Ubah, Sam Pam, Patrick Mancha, Ali Jeje, and a whole new set of players in the immediate past and present national teams of Nigeria.

That tap has not run dry. Jos is still breeding an endless stream of players immune from the city’s damaging reputation as the centre of ethnic, tribal, political and religious differences.

That’s what I remember as I recall the life of the ‘Field Marshall’.

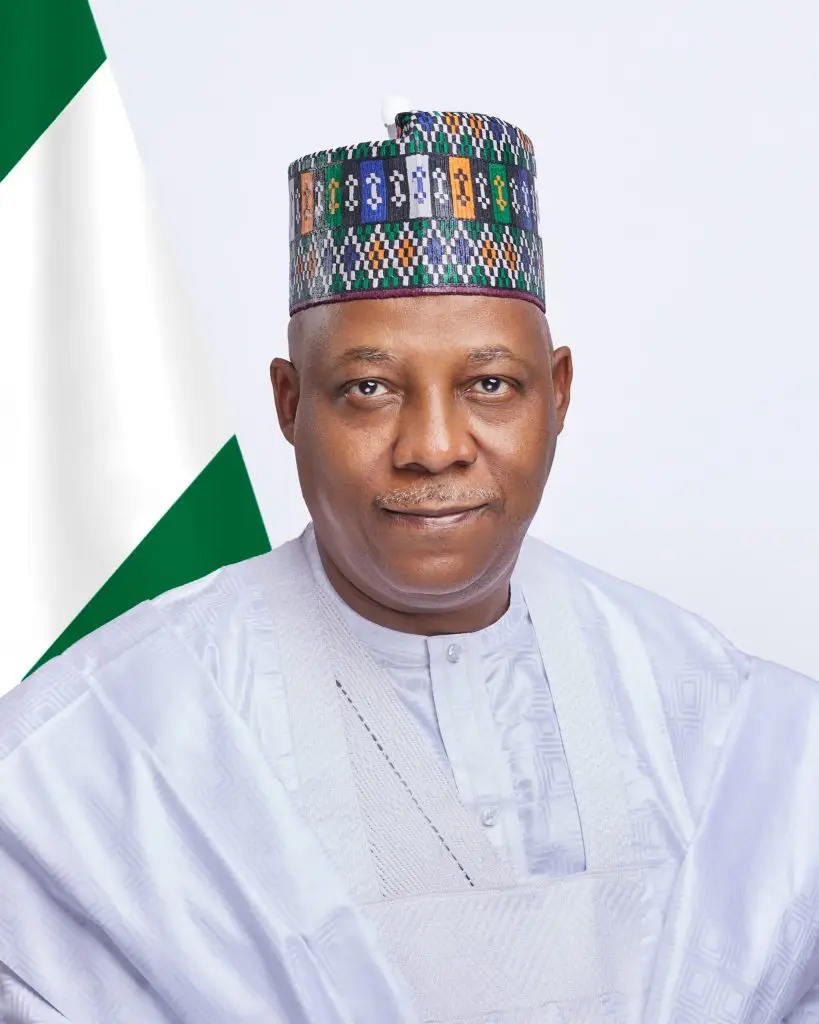

He was a Hausa man whose parents were originally from Kano, but spent all their lives in Jos. His dream, which he often shared with me, was for a way to be found by the governments to return the town to the Jos of old, the Jos we all grew up in, loved and lived in happily.

His nickname, ‘Field Marshall’ captured him aptly on the football field; how he played like a general commanding his troops from the rear; how he started most attacks with his smooth and elegant runs and passes up field; how he played with uncommon composure and calmness, a page from the book of the great German Libero, Franz Beckenbauer.

The Field Marshall was a delight to watch on the field, always cool and confident in his clean interceptions. Never wasting a tackle, always calculative, and a great organiser of his team, particularly his defence line. That’s why he was always made the captain of his various teams – Captain of St. Theresa’s Boys’ School, Jos; Captain of Academy Institute of Commerce, Jos; Captain of Mighty Jets FC and Plateau United FC; and, very briefly, Captain of the Green Eagles.

He turned to coaching after his illustrious playing career and became as good a coach as he was a player. His best achievements were his stint as Chief Coach of Nigeria’s women’s national team, the Falcons. His records speak. He is considered the most successful coach in Nigeria’s women’s football history.

That’s why his death, at 79 last week, was mourned by the entire country.

He had been downed by a freak domestic accident, a broken hip bone. He had called me up a few weeks ago and assured me he was feeling better. Then, the news of his death hit me like a hammer in the head, a humbling reminder again that none of us has any right to be alive whilst others die. Life is a privilege by the Universe for which we should always be thankful whilst we await our own turn at the gates of eternity.

Ismaila Mohammed Mabo, the Field Marshall, was one of the last surviving members of an era of national team footballers that went to represent Nigeria at the 1968 Olympic Games and almost conquered Brazil.

May he journey well back to his Creator!

Latest Comments