It was the summer of 1968, the period of long vacations in schools. I was a ‘toddler’ holidaying from Jos. I used to spend every summer holiday since the pogrom of 1966 between Lagos and Abeokuta.

I loved Abeokuta.

It was a quiet and laid back town. Abeokuta had always been a unique town with unique physical features, struggling not to be consumed by urbanisation, preferring to remain a retirement-base for its older indigenes who came back home to rest in the ‘evening’ of their lives having ‘gone, seen and conquered the world’ in their different fields.

1968-Abeokuta was populated mostly by students, their teachers, and retiree-indigenes. The middle-class is in very small supply except during some weekends when they would swoop on the town like hawks for social engagements.

One day, very soon, I shall write about Abeokuta beneath the surface, my personal take on the town, plus my incredible experiences.

So, let me return to that summer in Abeokuta ages ago with my late eldest brother, Dele Odegbami, nicknamed “Badmeat” because of his wicked defensive style of play on the football field. He was thè captain of Ebenezer Grammar School, a small private secondary school in Abeokuta, that rose from relative obscurity to become 1964 Western Nigeria Academicals champions of thè Thermogene Cup for all secondary schools in the region. That became the school’s greatest claim to fame with several of the players becoming household names in Abeokuta.

In the evening, a few days into this particular visit, I went with him for a football training session on the grounds of Abeokuta Grammar school. I don’t recall the team that was to train there, but on the ground was a gentleman marking the perimeter of the football field with a white liquid substance. There were a few students in school uniforms that were helping him. From the look of it the youngish-looking gentleman was a teacher.

As soon as he saw us, the gentleman hailed: “Baaadmeat”.

My brother replied: “Ameh”.

They obviously knew each other. He was about completing the work on the field when we arrived.

Soon, he was done. The football field was carved out of the environment like a work of art by the man my brother called Ameh, obviously a nickname that most people also called him. Permit me to refer to him also here by that name even though he would have been at least 8 years my senior if he was my brother’s classmate in their HSC class.

He joined us by the side of the field, instructing the students, and chatting animatedly with my brother.

He was indeed, a young teacher in the school, engaged as a sports officer one year after his HSC. It was common for bright HSC students to teach in secondary school after qualification in those days.

My brother introduced me to Ameh as his younger brother from Jos, and a great footballer. The football got Ameh’s attention and interest. Footballer? Was I thinking of changing schools and coming to Abeograms? How good was I?

My brother told him I was a striker and had been extremely impressive at our small- sided games in Iberekodo area of Abeokuta where we played 7-a-side football most evenings.

Ameh would not let go. He wanted to test me. Badmeat was apparently aware of this his antic. He would challenge players to score him from the penalty spot and put a wager on it. He had an awesome reputation as a stopper of penalty kicks. It was almost legendary. Many people believed he had supernatural powers, so the story went.

For my age, I was approaching 16 at the time, I was tall, thin and naive.

Badmeat boasted about my ability and told Ameh that he could not stop any of my 2 penalty kicks. Before I knew what was happening, my brother threw the challenge. Ameh never backed off such challenges. Looking back now, it is not impossible that the challenge involved some small amount of money between them, or just pride.

That’s how, innocently and without preparing for it I found myself wearing my brother’s Gola boots, and taking on the great Ameh, the goalkeeper with a mystical power to stop penalty kicks. Ameh had been Abeokuta Grammar School’s reserve first-team goalkeeper. He was also a member of the Abeokuta Town team that was made up almost entirely of students from the academicals.

Ameh quickly changed into his goalkeeping outfit and went into goal at one end of the field. Some students were attracted and started to gather around the goalpost area.

My heart, at this point was racing excitedly. I was good at taking penalty kicks and was confident. The wager aspect and the growing number of spectators were new to me. My inside rumbled from excitement to a gentle internal shiver.

The ball was placed on the penalty spot by Ameh himself. He moved backwards into goal. I positioned myself in front of the ball, and took my 4 steps backwards and to one side as Reverend Father Cotter had taught me at St. Murumba College, Jos, my mind racing between concentrating on recalling my well-rehearsed formular and watching the man prancing on the goal line in front of me. My inside kept rumbling. I must not let my brother down.

I looked up and the man in goal had stopped moving. He was standing on the goal line, but not in the middle as was won’t of regular goalkeepers.

He had moved at least one foot towards one side. There was a yawning gap on one side and a smaller gap that his outstretched arm could easily cover on the other.

He was now calling on me to take my shot.

What side do I kick the ball to? The question was racing through my head. To the right of the goalkeeper where he had deliberately left more space, or to try and shoot through the narrower space?

I stood there momentarily confused. I tried to read his intentions and his mind. Why would he leave one side so invitingly open? A good powerful shot to that side was a sure goal. Or was it?

I had never seen anything like that in my young age, for a goal keeper to deliberately stay more on one side of the goal line than the other. It provided an irresistible invitation. Or was this a trap? Was that his stronger side?

Was he tempting me to go there?

He would easily stop any ball directed to his right narrower space. The ball would be too close to the goalkeeper.

My mind was in confusion. My insides were now shaking like leaves.

My brother had not warned me, or told me anything. I did not know what to do. All my Father-Cotter lessons and rehearsals evaporated in those few seconds of indecision.

The blast of the whistle for me to take the kick ‘woke’ me up from my reverie.

I prepared to make my small run up to the ball thinking I had no choice but to shoot the ball hard towards the wide open space to Ameh’s left side.

The goalkeeper was obviously up to some trick. He was playing with my small mind. He knew I was confused. He knew there was no way I would not kick towards the wider space. He was watching me and beckoning on me to take my shot. At this point, I was quivering like a drawn bow.

The whole world was watching me and waiting for me to fail my ultimate test.

The area around the goal post area appeared to be lined by a ‘million’ students, at least!! My eyes were playing tricks too.

I started my run up to the ball. 2 steps into the run, the world changed. I don’t know if it was an illusion, or the wind playing wayo.

From the top of my eyes that had been mostly concentrated on the ball in front of me, I sensed rather than saw a movement.

I glanced up. Ameh was no longer where he was before my run started.

He had shifted half a foot or so to his left, reducing the size of the gapped ‘tooth’ in the goalmouth.

All my initial plans started to blow up in my face. The man moved ever so slightly, even more by the third step into my run up. I saw that slight movement clearly now.

That was no wide space any more to bury by shot easily.

I could not stop my forward movement to the ball. I had reached a point of no return and I had no plan B where to place my shot. The open space had disappeared by the time my right foot arrived at its destination. By the time my foot struck the ball I knew I had been suckered.

Ameh had played a psychological game with my innocent mind and won? He forced me to choose a side to kick to and blocked it at the end. It was now too late to go the other way. The the first law in taking penalty kicks is to pick a spot and never change your mind when striking the ball there.

I had fallen for the cheapest trick in the world of football, a very simple psychological set up. I had to learn my lesson the hard way, right in front of ‘millions’ of students that had gathered to see this young footballer from Jos humbled.

As I struck the ball, my eyes were closed in anguish, all plans collapsing like a pack of cards. I just blindly shot without any plan where it would end up. The roar of the spectators made me open my eyes. The man was laughing on the goal line. I was angry and mad. I must have passed out. Ameh had not even moved. There was no need to. The ball had sailed and flown like an inflated balloon into the evening sky, begging to be plucked down.

For the rest of that day my brother tried to console me. It was a lesson taught me by a thinking goalie. It stayed with me throughout my football career.

The following day, or two days later, Ameh told my brother to bring me to Ijeja stadium where the town’s team was training for an upcoming FA Cup match against Oyo town, or so. I went with him and met with Ameh again. This time he had words of consolation to offer me and a word on the winning psychology for the best strikers.

That weekend I was chosen to play in the Abeokuta team that was loaded to the hilt with great players that I got to know later.

There was one nicknamed Ojingolo. He was popular throughout the West. There were George Hassan, Kasali, the goalkeeper, Ogun, a great midfield player, Abraham, central defender, and others, all members of the academicals team of Western Nigeria.

That was my encounter with Ameh.

I had only casual contact with him during most of my football playing days and after, even though he was around, teaching football to students in schools and later in clubs. His best stints as a coach were with Wikki Tourists of Bauchi and Stationery Stores of Lagos. He was a very colourful, confident, eloquent, flamboyant, competent but highly loquacious coach.

He was like today ‘s Jose Mourinho. He used psychology a lot to impact his players and weaken opposing teams. His White handkerchief which he waved whenever he was entering a football ground was his ‘weapon’ of the mind games he played with opposing teams and their coaches.

The highest point of his coaching career were stints as Technical Director of the Nigeria Football Association, and as manager attached to the Gambian national team.

When Ameh was to set up his Pepsi-Academy, he visited my office in Yaba for the first time and shared the idea with me, seeing that I had started the All-Nigeria Secondary Schools Football Championship for the Shell Cup. He wanted my moral support.

We discussed the idea of establishing a football school also many years later. He expanded the Pepsi Academy project to include a football college arm. I established a multiple sports academy that was entirely education-based.

We met from time to time to discuss the schools and compared notes, always encouraging each other during the challenging times.

In the last few years, when I finally returned home to our mutual roots in Abeokuta, we would often meet along the social and traditional circuits.

Through the decades, since we first met in 1968, we had a fantastic relationship carved out of our first unforgettable encounter that memorable evening on Abeokuta Grammar School football ground when he taught me a useful lesson in football psychology that I would never forget.

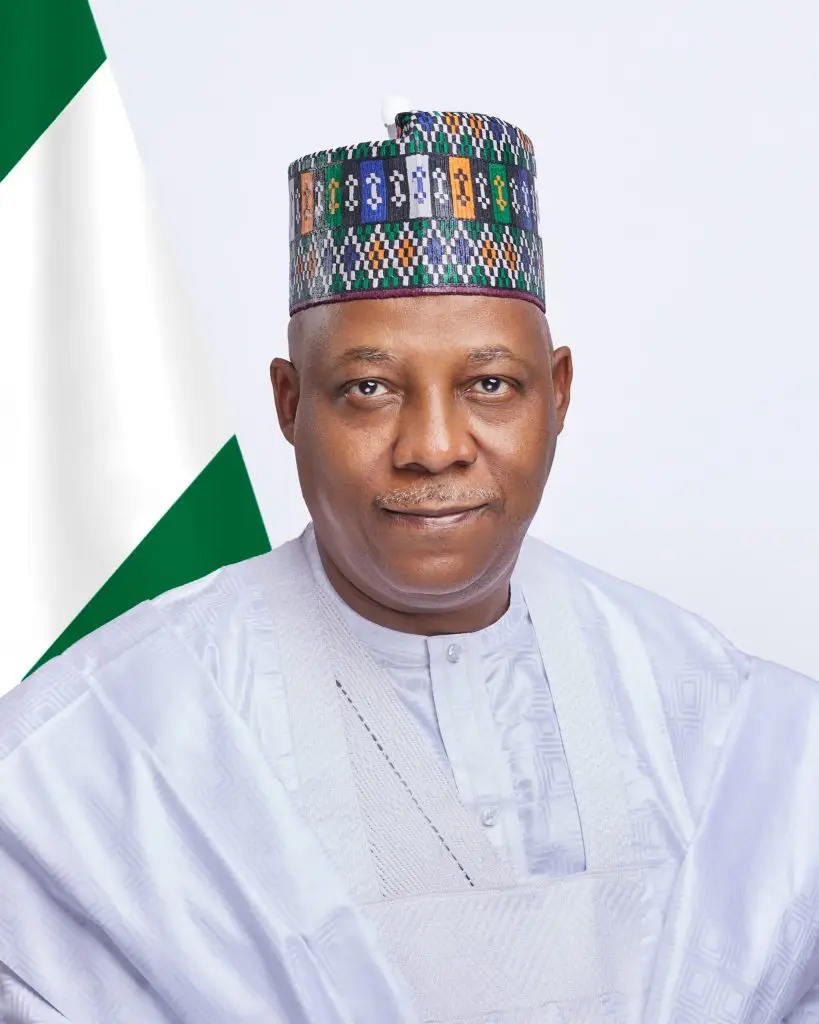

The Olori Parakoyi of Egbaland, Chief Kashimawo Laloko, alias Ameh, made his mark and left permanent imprints on the football development landscape of Nigeria. May he Rest in Peace!

Latest Comments